"The Temptation of Saint Anthony" (1946) by Salvador Dali (1904-1989)

By Chris Berry (@cberry1)

It is widely acknowledged that credit is the lifeblood of an economy. It provides the leverage for growth. The interest rate assigned to a fixed income security can then be thought of as the “cost” or “price” of the credit.

This makes sense as lenders want to ensure their assets (cash, typically) earn a return above the risk free rate. To be clear, there is much more to determining an interest rate, but this is the basic premise.

What happens, though, when that rate goes negative?

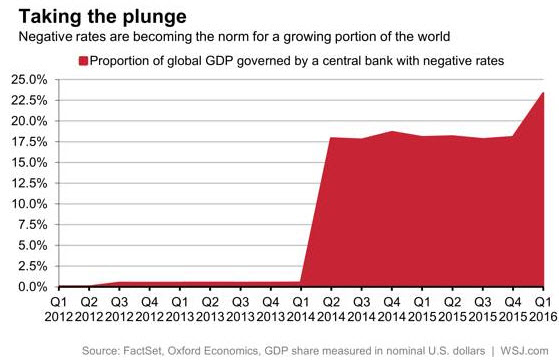

This note is a primer on negative interest rates, a phenomenon not unheard of, but increasingly en vogue in the wake of the Bank of Japan’s surprising (or maybe not so surprising) announcement to set the interest rate they charge commercial banks to deposit money at the BoJ at -0.1%. This follows the path set by the Danish central bank in 2012 and was soon followed by the European Central Bank in 2014 and the Swedish and Swiss central banks in 2015. According to the Wall Street Journal, now 23% of global GDP is operating in a negative interest rate environment. We can’t find any historical parallel here. The implication is that central banks, through policies such as quantitative easing, may have steered an interconnected global economy into uncharted waters as these measures haven’t spurred inflation and in fact may have accelerated deflationary forces.

What are negative interest rates?

A country’s commercial banks are able to essentially “deposit” their reserves with the central bank of that country and can earn interest. The central bank typically allows this as the deposits can earn interest and help the commercial bank in question bolster its capital base until it locates opportunities for lending. In a negative rate scenario, the central bank charges the charges bank who has parked their cash there for this “privilege”. This would be akin to your bank charging you to maintain a savings account and not offering any interest on the account balance.

This policy has been undertaken by various central banks to encourage lending and theoretically boost economic growth. Growth in the Euro Zone since 2010 on a quarterly basis:

Source: Bloomberg

ECB officials there instituted a negative rates policy in mid 2014. Has it worked?

In Japan:

Source: Bloomberg

Japan has famously struggled with deflation for two decades. This interest rate cut is the latest salvo designed to enhance growth and generate inflation. BoJ officials are blaming this move more on a weak global economy, exacerbated by sluggish trade and uncertainty with China rather than weakness in the Japanese economy. These charts show just how anemic growth has been and provide clarity into why these respective central banks have taken the step of essentially forcing banks to lend.

Is this step unprecedented?

As we said above, the central banks of Denmark, the ECB, Sweden, and Switzerland have introduced this policy in recent years (2012, 2014, and 2015 respectively) and the results are unclear. Each central bank had its own motives such as defending the currency in addition to trying to generate inflation. It appears that this move is borne more of desperation rather than sound and effective policy making. The goal is a targeted inflation rate of 2% and though the measurement is controversial, central banks almost everywhere are falling short of this goal and negative rates are one of the few options left. While the size of this move in Japan (around .1%) isn’t huge, the idea that an increasing number of banks are willing to resort to this tactic is significant. According to the Wall Street Journal,

“Never before have so many central banks explored sub-zero territory at the same time.”

Inflation rates in Japan are shown below (core CPI):

Source: Bloomberg

…and in the Euro Zone:

Source: Bloomberg

How will we know if it is working?

While the policy isn’t likely to affect the consumer on a day-to-day basis, watching inflation data as well as money multiplier data could be good clues. The real risks lie with the threat of moral hazard in that banks, now forced to lend, could go on a hunt for higher risk opportunities, putting their capital at significant risk. This is how bubbles are formed: cheap money looking for a higher return until interest rates “normalize”.

While we wait and see, a key area of focus is the government bond market. After the BoJ announcement last week, the US 10 Year Government bond nosedived to 1.92%, well below the psychologically important 2% level.

Source: Bloomberg

Any implications for the natural resource sector?

It’s unlikely that this small move will have any appreciable effect on the commodity sector. We view it as a stretch to believe that forcing commercial banks to lend and possibly search out risky projects could somehow rescue the commodity sector from its seemingly terminal decline. Ultimately supply and demand will rebalance, but negative interest rate scenarios imposed by central banks won’t be the catalyst. Paradoxically, this may benefit the precious metals somewhat as no yield is preferable to a negative yield.

This policy of negative rates raises more questions than it answers, and that may be the true danger here. Central bank policy has clearly diverged with the US Federal Reserve seemingly biased towards increasing, rather than lowering, interest rates in stark contrast to much of the rest of the world. Did the Fed make a historic mistake in December? Is a stronger USD a given now as China re-engineers its growth model and investors flee volatile financial markets?

We may be about to find out.

Chris Berry

President of House Mountain Partners LLC and Co-Editor of Disruptive Discoveries Journal

Chris Berry is a well-known writer, speaker, and analyst. He focuses much of his time on Energy Metals – those metals or minerals used in the generation or storage of energy. He is a student of the theory of Convergence emanating from the Emerging World and believes it will have profound effects across the globe in the coming years. Active on the speaking circuit throughout the world and frequently quoted in the press, Chris spent 15 years working across various roles in sales and brokerage on Wall Street before shifting focus and taking control of his financial destiny.He is also a Senior Editor at Investor Intel. He holds an MBA in Finance with an international focus from Fordham University, and a BA in International Studies from The Virginia Military Institute. Please visit www.discoveryinvesting.com and www.house-mountain.com for more information and registration for free newsletter as well as his disclaimer.

Our Thinking and What We Do

We are believers in the theory of Convergence. As the quality of life between East and West slowly merges due to advances in technology, continued urbanization, and changing demographics, opportunities across numerous industries will arise which we can take advantage of. We aim to point out the strategic opportunities in the commodity space which arise from these themes.

Throughout history, no society has sustained a higher quality of life without access to cheap commodities or materials. As global population increases, putting stresses on resource availability, efficiency and technology must come to the fore to continue to provide for a higher quality of life. The looming convergence of lifestyles between the emerging world and the developed world is a fact we must all understand and accept in order to chart a sustainable path forward for humanity.

The material herein is for informational purposes only and is not intended to and does not constitute the rendering of investment advice or the solicitation of an offer to buy securities. The foregoing discussion contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (The Act). In particular when used in the preceding discussion the words “plan,” confident that, believe, scheduled, expect, or intend to, and similar conditional expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements subject to the safe harbor created by the ACT. Such statements are subject to certain risks and uncertainties and actual results could differ materially from those expressed in any of the forward looking statements. Such risks and uncertainties include, but are not limited to future events and financial performance of the company which are inherently uncertain and actual events and / or results may differ materially. In addition we may review investments that are not registered in the U.S. We cannot attest to nor certify the correctness of any information in this note. Please consult your financial advisor and perform your own due diligence before considering any companies mentioned in this informational bulletin.

The information in this note is provided solely for users’ general knowledge and is provided “as is”. We at the Disruptive Discoveries Journal make no warranties, expressed or implied, and disclaim and negate all other warranties, including without limitation, implied warranties or conditions of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose or non-infringement of intellectual property or other violation of rights. Further, we do not warrant or make any representations concerning the use, validity, accuracy, completeness, likely results or reliability of any claims, statements or information in this note or otherwise relating to such materials or on any websites linked to this note. I own no shares in any companies mentioned in this note and have no relationships with any other companies mentioned.

The content in this note is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all matters and developments, and we assume no responsibility as to its completeness or accuracy. Furthermore, the information in no way should be construed or interpreted as – or as part of – an offering or solicitation of securities. No securities commission or other regulatory authority has in any way passed upon this information and no representation or warranty is made by us to that effect. For a more detailed disclaimer, please click here.